Whether they deliver fortune cookies, pick up garbage or take kids to school, trucks and buses are some of today’s hottest applications for electric vehicle technology. Old-school manufacturers, such as International, Kenworth and Mack, are scrambling to ramp up their assembly lines to compete against new startups vying for a piece of this lucrative market.

Several models are currently in limited production, with others due to begin rolling off assembly lines later this year. In fact, some experts believe that commercial vehicles will become the most widely produced type of EV during the next decade.

According to IDTechEx, the market for battery electric and fuel-cell electric trucks for medium- and heavy-duty applications will reach $203 billion by 2041. Much of that demand will come from China, Europe and the United States.

Approximately 28 million commercial vehicles currently roam the U.S., which represents about 10 percent of all vehicles and 28 percent of all carbon emissions from on-road vehicles. A recent report from the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) claims that electric buses and trucks represent the next frontier for electric vehicles.

When it comes to performance, electric trucks exceed their internal combustion engine counterparts. Photo courtesy Kenworth Truck Co.

Batteries typically straddle the frames of electric trucks, replacing fuel tanks. Photo courtesy Kenworth Truck Co.

By Austin Weber, Senior Editor

Medium- and heavy-duty electrified platforms offer numerous benefits to fleet owners.

Commercial Vehicles Go Electric

“Widespread electrification already makes sense for several classes of heavy-duty vehicles based on their operating characteristics, the range of today’s battery technologies, and similar if not cheaper ownership costs,” says Jimmy O’Dea, senior vehicles analyst at UCS. “Electric trucks emit 68 percent to 88 percent less life cycle global warming emissions than similar diesel trucks, depending on the type of vehicle.”

Last year, California took a big step toward addressing the issue when the California Air Resources Board passed the first statewide electric truck sales standard. It requires commercial vehicle manufacturers to sell a certain number of EVs each year beginning in 2024, resulting in 15 percent of trucks on the road being electric by 2035. Specifically, 75 percent of new Class 4 to Class 8 rigid truck sales and 55 percent of new tractor truck sales must be zero-emission by 2035.

Numerous Benefits

Electric vehicles offer many benefits to fleet owners, such as fewer emissions and much quieter operation compared to traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles. Those benefits are multiplied when truck fleets operate in or near congested urban areas.

An electric drive consists of fewer parts, with the electric motor being the only moving one, reducing the risk of breakdowns and the need for frequent servicing.

Tesla plans to start producing its much-anticipated Semi truck this year. Illustration courtesy Tesla Inc.

Electrification also boosts vehicle efficiency. Electric engine losses are significantly lower than a diesel engine’s. In addition, electric motors can deliver peak torque almost instantly, meaning they excel at towing heavy loads from a dead start or up a gradient.

“Electric trucks have numerous benefits that impact the bottom line of fleet operators, including a 75 percent reduction in energy costs and a 60 percent reduction in maintenance costs,” says Jason Gies, director of business development for e-mobility at Navistar International Corp. His company recently unveiled an electric school bus and will be launching a medium-duty electric truck later this year for pickup and delivery applications.

“Electrification in commercial vehicles is different from cars,” adds Marshall Martin, mobility industry analyst at Frost & Sullivan Inc. “So far, electric cars have been a niche segment that have a significant [markup that] only a few customers are willing to pay for.

“[However], when it comes to a commercial vehicle, customers only have one reason to own it: Can they make or save more money with it? It’s got to make business sense, and return on investment is a major factor in this.

“In recent years, with declining prices of batteries, motors and other EV components, the total cost of ownership parity between electric and internal combustion engine [buses and trucks] has come down significantly,” explains Martin. “Many OEMs are now confident that their customers can start making money on the added investment in three to five years.

Electric trucks offer many benefits to fleet owners, such as fewer emissions, quieter operation and less maintenance. Illustration courtesy Peterbilt Motors Co.

Volvo Trucks will be assembling the drivetrain of its VNR Electric model in-house. Photo courtesy Volvo Trucks

“Hence, we see a sudden surge in electric variant announcements from OEMs,” says Martin. “[This activity] will stoke a slew of launches in the next two to four years that will only grow in the future.

“As far as light commercial vehicles are concerned, we can expect a lot of commonalities between cars and Class 1 and 2 vehicles, such as vans,” notes Martin. “As far as heavier trucks are concerned, they will require bigger batteries and battery packs, and higher-powered motors and power electronics. But, the major difference is going to be with the architecture and placement of these components.

“Electric cars are largely expected to have a skateboard platform that supports the battery and are most likely to use wheel-hub or in-wheel motors going forward,” Martin points out. “For trucks, however, this could vary depending on the type of construction.

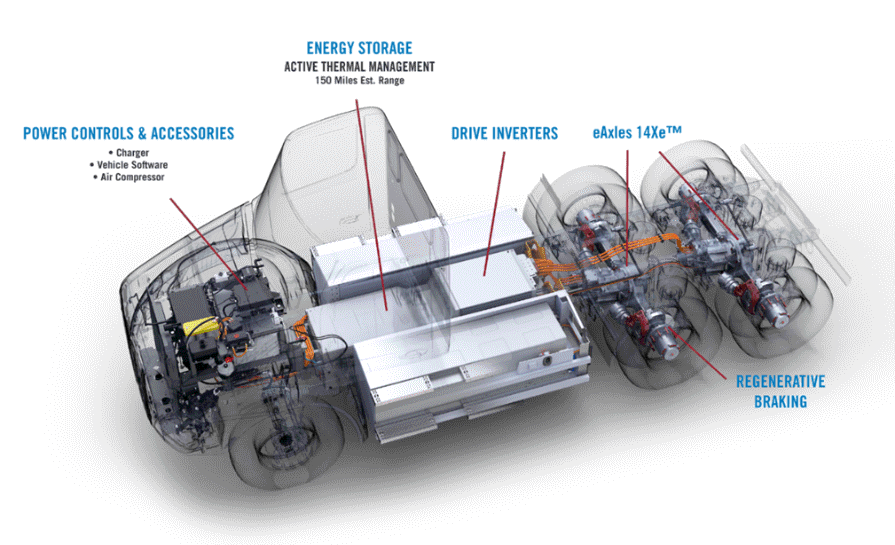

“If the EV is built from scratch, the platform will be fresh and batteries most likely placed underneath the cabin, with trucks using e-axles straight from the shelf,” says Martin. “If the EV is built on an existing ICE platform, batteries can be placed behind the cab in between the ladder frame or on the side rails where gas tanks are traditionally placed.

“Most of these trucks will start off using centrally driven motors,” claims Martin. “However, in the coming years, architectures will evolve and have separate platforms for EVs that are more efficient.”

One of the hottest segments of the electric truck market is medium-duty (Class 3 to 6) vehicles, such as step vans and delivery vehicles that are used by companies such as Amazon, DHL, FedEx, Peapod and UPS.

This heavy-duty e-axle will be used on Class 8 Kenworth and Peterbilt trucks. Illustration courtesy Meritor Inc.

“This segment is an ideal use case for electrification and will be one of the first ones to be electrified because of the duty cycle,” says Martin. “Limited daily driving range anywhere between 60 to 120 miles will be minimum range offered by OEMs on these vehicles. Frequent starts and stops [also benefit from] regenerative braking.

“In terms of performance (energy efficiency, power and torque), electric trucks exceed their ICE counterparts, but challenges prevail on the size and cost front,” explains Martin. “In the heavy-duty truck market (Class 7 to 8), electric vehicles powerful enough to haul semi-trailers over long distances have several technical issues that still need to be addressed before they give diesel-powered machines serious competition.

“When it comes to heavier trucks, the impediments to electrification depend on application and duty cycle,” claims Martin. “For short-regional haul, vocational and local distribution (routes that cover less than 300 miles per day), cost will be a major hindrance.

“For long-haul highway trucks, cost should not be the biggest hindrance,” adds Martin. “The major challenge is going to be range, as truckers can easily do anywhere between 400 to 600 miles a day. That’s [challenging] for OEMs to provide without compromising on payload. Another issue that needs to be resolved is the availability of charging points on highways.”

Truck Trends

Many truck manufacturers have recently unveiled a variety of electric models intended for different market segments. They’re trying to stave off new competition from start-up companies such as Arrival Ltd., Cenntro Automotive, Lion Electric Co., Nikola Motor Co., Tesla Inc. and Tevva Motors Ltd.

“Those new-age, pure-play companies have pushed the traditional powerhouses into not only taking a fresh look at electric vehicles, but also expediting their respective EV launches,” says Martin.

One of the most anticipated models is Tesla’a Semi long-haul truck, which is scheduled to go into production sometime this year. Among other features, Tesla claims the vehicle will be capable of accelerating from 0 to 60 mph without a trailer in 5 seconds, compared to 15 seconds in a comparable diesel truck. It will also be able to accelerate from 0 to 60 mph in 20 seconds with a full 80,000-pound load vs. 60 seconds for a traditional truck.

If Tesla can deliver the vehicle with a 500-mile range (recent reports claim it can go up to 621 miles per charge with next-generation battery technology) and a price of $150,000, then it has the potential to disrupt the conservative trucking industry. So far, Tesla has racked up hundreds of reservations from companies that operate large nationwide distribution fleets, such as PepsiCo, UPS and Walmart.

All of that buzz has attracted the attention of industry leader PACCAR Inc., which produces trucks under the DAF, Kenworth and Peterbilt nameplates. It recently unveiled the Kenworth K270E, K370E and Peterbilt 220EV, which are Class 6 to 7 vehicles targeted at local drayage applications such as food and beverage distribution.

Several companies plan to produce electric garbage trucks. Photo courtesy Mack Trucks Inc.

The Kenworth battery-electric vehicles offer two direct-drive motors rated at 355 and 469-hp, depending on application. The electric power train is available with high-density battery packs of 141 and 282 kilowatt hours (kWh) that deliver up to 100 and 200-mile range, respectively. The vehicles are assembled at Kenworth’s plant in Mexicali, Mexico, which produces conventional versions of the K270 and K370 cabovers.

This year, PACCAR will also begin producing Class 8 day cab trucks, such as the Kenworth T680E and the Peterbilt 579EV for regional haulage applications. They are available as either a tractor or straight truck in a 6x4 axle configuration.

Suppliers such as Dana Corp. and Meritor Inc. produce the electric drivetrain components for the PACCAR EVs. For instance, Dana has developed e-axles and driveshafts as part of its Spicer Electrified e-Power (battery packs, battery management and onboard charger) and e-Propulsion (motor and inverter) system, which are used in the Kenworth and Peterbilt Class 6 and 7 trucks. The Class 8 vehicles feature Meritor’s Blue Horizon 14Xe tandem electric power train.

Volvo Trucks is using more of a vertical integration strategy for its recently unveiled VNR Electric, which also goes into production later this year. The electric truck is designed for driving cycles with local and regional distribution ranges.

Volvo is purchasing 264-kWh lithium-ion batteries that charge up to 80 percent within 70 minutes and have an operating range of up to 150 miles based on the truck’s configuration. Its proprietary electric driveline, rated at 455-hp, generates up to 4,051 ft.-lb. of torque.

“The VNR Electric will be assembled at our New River Valley plant in Dublin, VA,” says Brett Pope, director of electric vehicles at Volvo Trucks North America. “The drivetrain will be made in-house at our facility in Hagerstown, MD.”

Volvo’s Mack Trucks division has also jumped on the EV bandwagon with its LR Electric model for waste disposal applications. From the outside, the vehicle looks similar to the diesel Mack LR, but with a few minor changes inside the cab, such as gauges and switchgear.

The truck is equipped with four lithium-nickel manganese cobalt oxide batteries and two electric motors that produce a combined output of 536-hp. Starting this year, the LR Electric will be built at Mack’s Lehigh Valley Operations facility in Macungie, PA, where all of the company’s Class 8 trucks are assembled.

Assembly Lines Ramp Up

Most truck manufacturers plan to produce electric vehicles in the same factories that assemble traditional diesel-powered models. However, while production processes will look similar, engineers are busy laying out new flexible assembly lines and streamlining work flows.

Many electric trucks, such as the Mercedes-Benz eActros, models will be assembled alongside vehicles with ICE engines and power trains. Photo courtesy Daimler AG

About the Author

Austin has been senior editor for ASSEMBLY Magazine since September 1999. He has more than 21 years of b-to-b publishing experience and has written about a wide variety of manufacturing and engineering topics. Austin is a graduate of the University of Michigan. Author image courtesy of Weber.

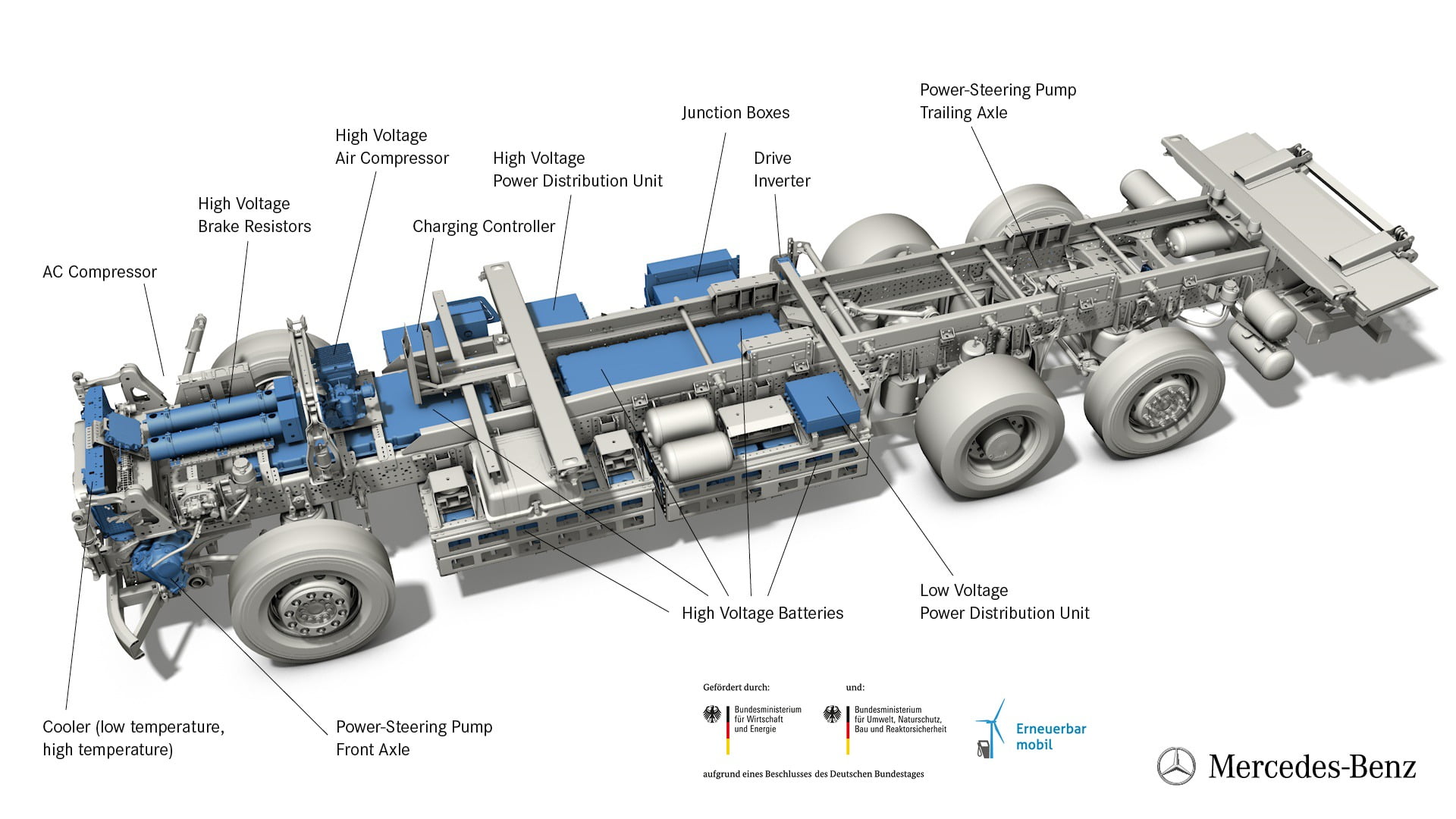

Daimler AG has set a target for 2039 of tank-to-wheel CO₂ neutrality for all new vehicles it sells in Asia, Europe and North America. Ground zero in its ambitious quest is the Mercedez-Benz Trucks factory in Worth, Germany. It is currently in the process of ramping up to mass produce the eActros model this year, followed by the eEconic next year.

“Electromobility will open up new opportunities for employees in the production process, as a new range of tasks and job profiles will emerge as a result,” says Matthias Jurytko, plant manager. “Preparations are in full swing to get our production ready for the demands associated with electric drive systems. For example, we are currently training our [assemblers] in the field of high-voltage systems, a fundamental area of expertise as far as the assembly of automotive batteries and the construction of electric trucks is concerned.

“The electric truck models will be assembled alongside trucks with conventional drives in a flexible process,” explains Jurytko. “The construction of the different vehicle types [will] be integrated as far as possible, with the basic vehicle structure being built on one line regardless of whether it will be getting a conventional combustion engine or an electric power train.

“Certain modifications will be made to the production process to accommodate the different types of vehicles,” Jurytko points out. “The installation of various nonconventional drive components will take place in a separate process, as will the assembly of the electric power train for the eActros.

“The centerpiece of the [e-truck] manufacturing process is going to be the production hall in building 75,” says Jurytko. “For around a year, work has been going on to convert the building and prepare it for the new production processes.

“This includes setting up a new assembly line on which the construction of all the electrical architecture of the eActros, in particular the high-voltage components, will take place, as will its initial operation,” explains Jurytko. “Subsequently, the vehicles will be fed back into the regular production process for finishing and final inspection.”

Daimler Trucks North America is also getting ready to ramp up production of electrified buses and trucks for its U.S. brands such as Freightliner, Thomas Built and Western Star. For instance, Thomas Built Buses Inc. has started to assemble Saf-T-Liner C2 Jouley vehicles at its plant in High Point, NC.

Freightliner EVs will include the eCascadia, a Class 8 tractor designed for local and regional distribution, and the eM2, a Class 6 to 7 truck designed for local pickup and delivery applications. Daimler will produce the eCascadia at its assembly plant in Cleveland, NC, while the eM2 will be built at its nearby facility in Mount Holly, NC.

Because electric trucks rely on fewer mechanical parts, they require less maintenance. Illustration courtesy Daimler AG

About the Author

Austin has been senior editor for ASSEMBLY Magazine since September 1999. He has more than 21 years of b-to-b publishing experience and has written about a wide variety of manufacturing and engineering topics. Austin is a graduate of the University of Michigan. Author image courtesy of Weber.

Another leading U.S. truck manufacturer, Navistar, also has a German parent. The company is part of the Traton Group, which is the truck division of Volkswagen AG that includes leading European brands such as MAN and Scania. Navistar recently established a new business unit called NEXT eMobility Solutions that is focusing exclusively on zero-emission vehicles.

Navistar’s first EV offering is the CE Series electric school bus that’s assembled at its Tulsa, OK, factory. The first buses were recently deployed in British Columbia.

Next in line will be a medium-duty truck that’s due for launch this fall. The International eMV Series is based on the diesel-powered MV Series. The truck’s 321-kWh battery and electric motor will generate a peak power of more than 474 kilowatts. Navistar believes that customers will be able to travel up to 250 miles on a single charge.

The company plans to build the eMV and future electrified models at its existing assembly plants. And, when its new state-of-the-art factory in San Antonio opens early next year, the first truck down the line will be an electric model.

The 900,000-square-foot facility will feature cutting-edge Industry 4.0 technology, such as predictive quality and maintenance, that will enable data-driven decisions to be made on the plant floor in real time.

“Our new plant in San Antonio will make assemblers’ jobs easier,” claims Mark Hernandez, senior vice president for global manufacturing and supply chain at Navistar. “We hope to achieve a 25 percent to 30 percent improvement in our hours per vehicle, based on the design and workflow of the plant.

“We’re going to build electric and diesel vehicles on the same assembly line,” says Hernandez. “Flexible workstations and advanced technology will enable us to ensure each vehicle that comes off the mixed-model line goes right to the correct testing station.

“Having a dedicated EV facility creates a lot of waste,” adds Hernandez. “With a mixed-model diesel and electric assembly line, if the EV market takes off, we can keep up with demand by replacing a diesel truck with an electric one. With mixed-model manufacturing, we’re able to react to the market. We don’t have to start at low volumes and then ramp up.”

Navistar’s new assembly plant in San Antonio will feature cutting-edge Industry 4.0 technology. Illustration courtesy Navistar International Corp.